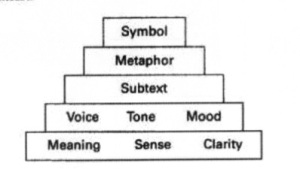

Theme is among the most mysterious and powerful elements of storytelling. In the classic pyramid of writing skills from the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, theme stands at the pinnacle. Theme is represented by symbols in that pyramid, the icons such as candles in a story about being lost. Even though it’s at the top of that diagram, theme is the nuclear reactor, the molten magma of your story. It’s also got another superpower. Theme, and knowing yours, makes writing your queries easier.

Theme is among the most mysterious and powerful elements of storytelling. In the classic pyramid of writing skills from the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, theme stands at the pinnacle. Theme is represented by symbols in that pyramid, the icons such as candles in a story about being lost. Even though it’s at the top of that diagram, theme is the nuclear reactor, the molten magma of your story. It’s also got another superpower. Theme, and knowing yours, makes writing your queries easier.

If you’re just writing for the first time on a story, book, or script, theme will be lurking under the surface. Your motivations for your characters are your primary concerns in early drafts. The needs and conflicts of the characters drive your plot. Remember that plot is about events, and story is about yours characters and how they change. When you consider what each character needs, you may find the needs can align around a bigger idea. Freedom. Justice. Redemption. That sort of thing. Some characters oppose the theme to provide conflict, too.

The Da Vinci Code is about the power of knowledge versus the power of the Church. The Great Gatsby is about the American dream and how it fails. Your theme can be downbeat as well as uplifting. Lonesome Dove is about the power of friendship and it can push a man across a new frontier of his life.

The gift that theme gives to query is better focus. In a good query letter you have to sum up your story relentlessly. What’s the book about? You begin the task of answering by writing a synopsis. Then it becomes a paragraph. Finally, it’s tight enough to state in a single sentence. It’s hard to do, but you’re the best person to find your theme. You’ve lived with the story longer than anyone. You knew what you meant to convey with your book. Not the telling part; that’s plot. You want to convey a feeling, because the feeling is central to unlocking the meaning of the story.

Theme usually emerges later in the creation process. It’s almost like you have to write a draft all the way through to understand what you were meaning to show with the story. Theme then becomes a good tool to polish and pare down and redirect a story.

Answer these questions to discover a theme under the surface of your storytelling.

- What stories are you drawn to the most? What issues do you struggle with in your own heart?

- Why do you feel compelled to tell this story?

- What is this story about if what happens is…

Your characters’ voices will sound clearest when you listen for theme. Let them report on the theme. Write what they’ll ask about their challenge.