Sooner or later you’ll hear about writers using Scrivener. It’s a writing tool that makes projects flow faster and increases your production. You write more, and faster. You find what you’ve written easier. It’s only $40, and your writing in it will live on your laptop (you can back up to the cloud, if you want.) Using it for the first 30 days is free. Download it for free here.

You’ll also hear that Scrivener is complicated. Hard to get started with, and full of a lot of features that are hard to understand, let alone use. You might have heard that same thing about Microsoft Word, too, once upon a time. Look how simple you can make Word. Scrivener can be just as simple. And like Word, you can reach for the deeper features if you want.

You don’t need to reach, though, in order to make Scrivener turbo-charge your creativity. There are only five steps to start writing in Scrivener, once you open the program for the first time. These First Five will give you chapters and even printed pages, if you need those these days.

Step 1. Start by launching your first project. Projects are the big box that everything for a book lives in. Project=book. “My Debut Novel” is a good name.

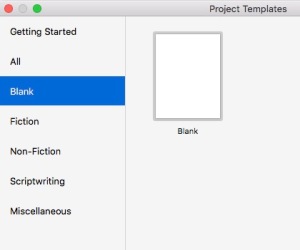

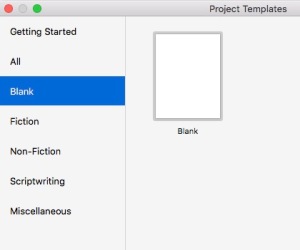

Action: When the program starts, the “Project Templates” window (above) opens. Click on “Blank” to the left, then double-click on the white page to the right. Name your project. You’ve now made your big box.

Important: Avoid the roadblock of choosing special Templates right away. Blank is good. Fiction, Nonfiction; all of that is for later. Using them right away will make Scrivener harder to learn. Choose Blank.

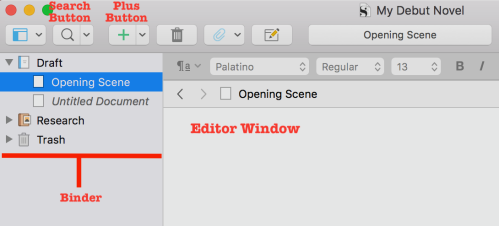

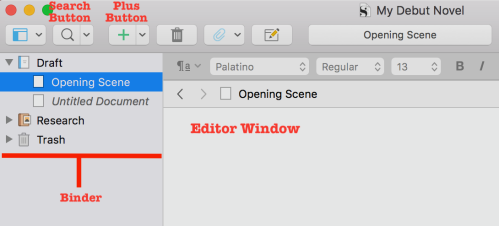

Step 2. Scrivener always opens with the Binder on the left. The Binder is important because you’ll see all of your book’s parts in it. Name your first document; nlick where it says “Untitled Document” and rename it. “Chapter 1” or “Opening Scene.” Names don’t matter now; you can change them.

Action: Click on “Untitled Document” and rename it, then hit return.

Step 3. Start to write your book. The cursor is already inside what Scrivener calls the Editor window. Look — you’re already writing! Scrivener auto-saves. You can play with the fonts (right above your writing in the Editor Window) just like in Word. Or not.

Action: Start writing. Have fun. Watch the word count in the bottom of the window swell.

Step 4. Written enough of your scene, or chapter? Make the next one.

Plus Button

Action: Click on “Draft” in the Binder on the left. When it’s highlighted, click on the Plus + button, right overhead on that tool bar. A new document (scene, chapter, section) is created, right under the first one. Go to work and write in the editor again.

Step 5. Print a document

Action: Click on the document in the Binder you want to print. Go up to the Edit menu and select “Print Current Document”.

That’s all you need. As you write, you will be creating a set of book pieces in that Binder, using the Plus Button. This is your book in its earliest draft. You can see the pieces. If you write longhand and have sections, just transcribe them into new documents you’ll make with that big + button.

Lather, rinse, repeat. Your writing is now all in one place. If you quit Scrivener, it will start up again with the big box (project “My Debut Novel”) you were working on last time. It will even go to the last document you were writing in.

You can do countless things with the Binder. Or something called the Inspector (the blue i on the top right). Don’t worry about those right now. You don’t need them to draft or revise. Once you want to share your writing, or shuttle it into Word, there are other steps to use. Only a handful, too. That’s for another blog.

Scrivener is a tool for writers at all levels. It makes it difficult to mislay writing you did, and makes it easy to compare versions and even passages. To find characters in scenes. So much more A lot. But these five steps get you writing, and drafting inside of Scrivener.

Okay, you have other questions.

Inspector

What are all those buttons, like the blue i?

At first you only care about the Plus button, the Magnifying Glass button (for searches)—and maybe the Inspector (Blue i) button. The Inspector will tell you when you created a document and when you last updated it.

Keep it simple for now. That Plus button can also make folders, but you probably don’t need them just yet.

What is a “Binder?”

It’s your road map, the address book, the list of pieces of your project, running all down the left-hand column. These are the doors. Your writing is inside them. Click one to select. Keep the Binder open at first, so you can jump from piece to piece.

Do I have to “compile?”

Only when you are truly, truly finished and ready to publish your book. Or, perhaps to share a bunch of scenes or chapters as a single file for your workshop group.

Go ahead, download Scrivener and try it out with the five steps. Start writing more and faster.

The #MeToo movement, also called a moment, has delivered many disturbing ones over the past months. Men have been forced to face their history with the women in their lives, and for some of them, it’s a history of failures. There’s not an ending coming for this movement anytime soon. It would seem the only repair is to raise a new generation of men who see these violations to be as senseless as genocide.

The #MeToo movement, also called a moment, has delivered many disturbing ones over the past months. Men have been forced to face their history with the women in their lives, and for some of them, it’s a history of failures. There’s not an ending coming for this movement anytime soon. It would seem the only repair is to raise a new generation of men who see these violations to be as senseless as genocide.

A fledgling memoir writer asked me about the prospects for transforming his work into a book. Within a couple of messages on LinkedIn, he squelched his own efforts. His book idea, about a single year of biking 5,207 miles, seemed too dim to work on. “I just doubt many would read it, even if published on Amazon. If there’s no audience, what’s the point?”

A fledgling memoir writer asked me about the prospects for transforming his work into a book. Within a couple of messages on LinkedIn, he squelched his own efforts. His book idea, about a single year of biking 5,207 miles, seemed too dim to work on. “I just doubt many would read it, even if published on Amazon. If there’s no audience, what’s the point?”